The massive cyber attack that affected the shipping behemoth Maersk happened in June 2017. Malicious spyware locked files on employee computers, putting an end to all port operations for Maersk. 76 port terminals were closed as a result of the attack, despite Maersk’s allegedly swift response, costing the corporation $300 million.

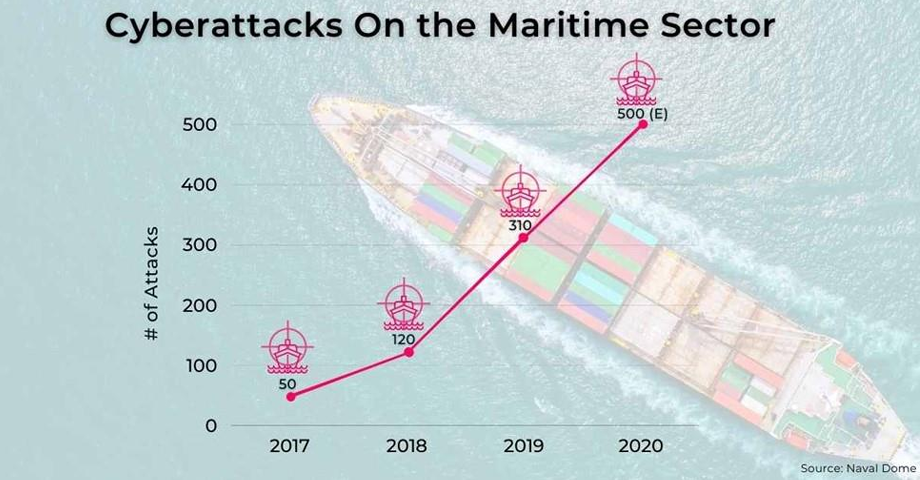

In recent decades, the digitalization of commercial shipping has advanced significantly. There has been a renewed drive for automation due to issues with the supply chain, green technologies, and industry-wide expenses. Although it presents a sizable new target for

cyberattacks, this promises increased efficiency. We’re quickly approaching a stage where it will be possible to digitally hijack a container ship on the high seas, just as the internet once appropriated the term “piracy” from the maritime domain.

The International Maritime Organisation should provide detailed guidelines and standards for safeguarding big autonomous networks, including a list of especially vulnerable systems, in order to mitigate this risk. The International Maritime Organization’s ability to

implement international maritime law has been contested by many. However, its recommendations have been successful in fostering agreement and bringing about particular adjustments in the international shipping sector. Significant changes to the current cyber

security landscape will be needed to cooperate with port authorities, shipping corporations, and national governments. Environment of threat will keep changing. In order to survive, the maritime sector must find solutions to new cyber security problems.

Potential Security Flaws:

Many systems on commercial ships are already set up to be vulnerable to cyberattacks. System vulnerabilities are typically classified as either affecting information technology or operational technology. Operational systems deal with the hardware and software onboard a

vessel, whereas information systems deal with data and business information.

The Maersk hack was mostly determined to be an information system attack, only having a little impact on ships via business-side delays and modifications. Ship operations use a limited set of commercial data and information systems when navigating maritime spaces.

Therefore, operational systems are the main focus of concern with regard to onboard cyber security. This divide is fast fading away, though, as interconnection becomes more prevalent and essential.

A tight eye on what happens on each ship and the activities of workers is a crucial aspect of the industry because billions of dollars’ worth of commodities cross the ocean every day. Each of the world’s largest commercial ships is equipped with essential operational systems,

such as global positioning systems (GPS), automatic identification systems (AIS), and electronic chart display and information systems (ECDIS), which enable sophisticated navigation. These electronic networked systems make up the traditional operational cyber

attack surface area together with a few other navigation and communication systems (such as radar, NAVigational TEleX, and dynamic vessel positioning).

On conventionally networked ships, physical onboard penetration is the most efficient assault method. Physically based systems continue to be threatened by intrusions onboard ships and sophisticated at-sea piracy. Because reckless use of USB-based storage devices can

introduce malicious malware into onboard systems, physical infiltration can occur even before a ship docks at a port. Ships can be forced off course by manipulating chart display systems, which can cause significant delays best case scenario and intentional ship crashes worst case. Numerous vulnerabilities that are reasonably simple to attack were discovered during penetration testing of the systems used by major chart manufacturers.

Along with direct access to individual ships, important operational subsystems are networked to one another via internationally standardised protocols, specifically the National Marine Electronics Association (NMEA) communication standards. An individual or group that can access one ship can probably already access countless other ships thanks to the standardization of shipborne control networks under unified protocols. Global positioning systems, steering, propulsion, and other subsystems are all controlled by the industry standard NMEA 0183.

There are serious risks associated with the transition from intraship remote networking to physical cable connectivity. Many techniques, including as physical computer-based assaults and, more recently, remote attacks, may be used to readily access NMEA 0183. On

contemporary boats, remote network infiltration or phishing attempts are possible, but physical entry is usually the most effective way to access operational systems. For this reason, current advice on cyber security “begins with the crew.” While these guiding principles remain valid, their applicability has begun to diminish with increased connection.

New Advice for New Dangers:

It is not unprecedented for autonomous ships to increase cyber security risks. Independent researchers are actively developing security frameworks, and a wide range of actors are attempting to contribute. To their credit, independent research and guidelines on self

sufficient cyber security have been released by the International Chamber of Shipping, the Digital Container Shipping Association, and the International Association for Classification Societies. NATO released a research on cyber security as recently as 2022, but it did not include

instructions for the construction of autonomous ships. It did, however, include explicit analysis of operational and information systems.

Nevertheless, there remains a significant void in the International Maritime Organization’s guidelines. This entity has an important duty to carry out in its capacity as a UN organization. Cybersecurity guidelines that provide a comprehensive overview of potential vulnerabilities in shipping are published by the International Maritime Organization. Two references to automation may be found in the introduction of the organization’s most recent version of its guidelines. Despite the fact that advancements in autonomous ship technology are happening more quickly every year, the new International Maritime Organization standards for 2021–2022 do not contain updated guidelines for the automated maritime environment.

In order to remain ahead of the curve, the International Maritime Organization needs to anticipate and adjust more quickly than in the past. New cyber security risk standards for autonomous ships were one of the topics of discussion during the 107th session of the Maritime

Safety Committee of the International Maritime Organization, which was held in June 2023. The current information/operational distinction has not been re-examined, nor have any new guidelines been released. Rather, it is reinforced by the Maritime Safety Committee’s cyber risk management guidelines. The idea that information and operations will always be distinct and incompatible should be abandoned by the International Maritime Organization in order to address cyber threats.

By comprehending how information and operational technology are convergent, shipping businesses as a whole as well as individual companies can strengthen their defences against cyberattacks. Cyber guidelines from the International Maritime Organization are still

only suggestions. Nonetheless, they have the potential to highlight the necessity of network encryption and the separation of instruments that are essential to operations, thereby encouraging the business to enhance its procedures.

The ideal outcome would be binding legal guidelines established by the International Maritime Organization Legal Committee. If nothing else, guidelines from the International Maritime Organization can highlight the hazards that are unique to autonomous ships and promote more frequent risk assessments. Secure autonomous shipping faces a dismal future if its cyber security guidelines do not keep up with the growing number of cyber-attack vectors.

Author: Amar Bahadur Budhathoki Chetri, Junior Engineer